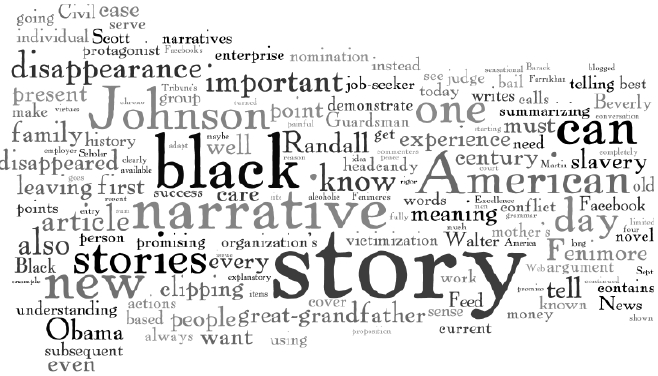

The cover article of the current issue of American Scholar, published by the Phi Beta Kappa Society, carries the headline “The End of the Black American Narrative,” with this subhead:

A new century calls for new stories grounded in the present, leaving behind the painful history of slavery and its consequences

(Not surprisingly, Barack Obama is pictured on the cover and on the Web page carrying the article, and it thus seems appropriate to publish this entry on the day Obama accepts the nomination of his party for President of the United States).

Here is how author Charles Johnson, the S. Wilson and Grace M. Pollock Professor for Excellence in English at the University of Washington, Seattle, characterizes the current black American narrative:

It is a very old narrative, one we all know quite well, and it is a tool we use, consciously or unconsciously, to interpret or to make sense of everything that has happened to black people in this country since the arrival of the first 20 Africans at the Jamestown colony in 1619. A good story always has a meaning (and sometimes layers of meaning); it also has an epistemological mission: namely, to show us something. It is an effort to make the best sense we can of the human experience, and I believe that we base our lives, actions, and judgments as often on the stories we tell ourselves about ourselves (even when they are less than empirically sound or verifiable) as we do on the severe rigor of reason. This unique black American narrative, which emphasizes the experience of victimization, is quietly in the background of every conversation we have about black people, even when it is not fully articulated or expressed. It is our starting point, our agreed-upon premise, our most important presupposition for dialogues about black America.

Johnson begins his argument by analyzing just what a story is, asking:

- How do we shape one?

- How many different forms can it take?

- What do stories tell us about our world?

- What details are necessary, and which ones are unimportant for telling it well?

- Does the story work, technically?

- And, if so, then, what does it say?

These are the questions he tells his students they must ask of a story, adding that a story must offer “a conflict that is clearly presented, one that we care about, a dilemma or disequilibrium for the protagonist that we, as readers, emotionally identify with.”

Does the black American story meet the criteria? Yes, Johnson says, it “beautifully embodies all these narrative virtues.”

Johnson builds his argument by summarizing the horrors of slavery and subsequent oppression. He calls the Civil Rights Movement “the most important and transformative domestic event in American history” after the Civil War. In sum, “The conflict of this story is first slavery, then segregation and legal disenfranchisement. The meaning of the story is group victimization, and every black person is the story’s protagonist.”

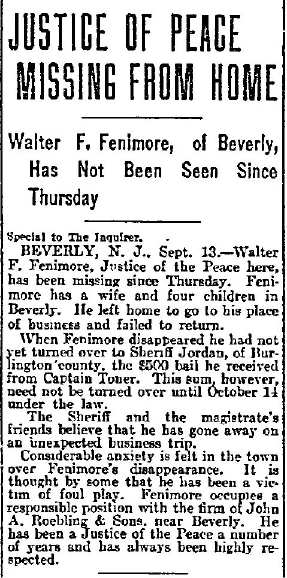

Johnson invokes the words of W.E.B. DuBois and the success of today’s prominent African-Americans (such as Obama and Oprah) to “challenge, culturally and politically, an old group narrative that fails at the beginning of this new century to capture even a fraction of our rich diversity and heterogeneity.” He critiques Louis Farrakhan and discusses a scholarly debacle in which a 19th Century black woman writer turned out to be white, “a cautionary tale for scholars and an example of how our theories, our explanatory models, and the stories we tell ourselves can blind us to the obvious, leading us to see in matters of race only what we want to see based on our desires and political agendas.”

I am vastly oversimplifying here and drastically summarizing when I’m longing to paste the whole article into this space. Bottom line: It’s an important article not only for what it says about Black Americans but for what its says about story and narrative.

And what narrative should replace the existing one? Johnson writes:

In the 21st century, we need new and better stories, new concepts, and new vocabularies and grammar based not on the past but on the dangerous, exciting, and unexplored present, with the understanding that each is, at best, a provisional reading of reality, a single phenomenological profile that one day is likely to be revised, if not completely overturned. These will be narratives that do not claim to be absolute truth, but instead more humbly present themselves as a very tentative thesis that must be tested every day in the depths of our own experience and by all the reliable evidence we have available, as limited as that might be. … These will be narratives of individuals, not groups. And is this not exactly what Martin Luther King Jr. dreamed of when he hoped a day would come when men and women were judged not by the color of their skin, but instead by their individual deeds and actions, and the content of their character?

Certainly Obama’s acceptance tonight of the presidential nomination (on the 45th anniversary of King’s “I Have a Dream” speech) is a triumph of the individual.

I’ve been writing recently about telling organizational stories in “About Us” pages, but, of course, “About Me” pages, seen most often in blogs, serve a similar purpose and come off best when told in story form (which I realize this blog’s “About Kathy Hansen” really doesn’t. Must fix that).

I’ve been writing recently about telling organizational stories in “About Us” pages, but, of course, “About Me” pages, seen most often in blogs, serve a similar purpose and come off best when told in story form (which I realize this blog’s “About Kathy Hansen” really doesn’t. Must fix that).