Reinvention Summit 2 is history, but I’m continuing to recap, synthesize, and expand on its 20 excellent sessions.

When Jeff Gomez, arguably the best-known figure in transmedia storytelling, talks about creating storyworlds — he is, on one level, talking about “properties,” the brands like Disney’s Pirates of the Caribbean and Mattel’s Hot Wheels for which his company, Starlight Runner Entertainment, created transmedia products. (By the way, get a good feel for how transmedia storytelling works with these properties and what it looks like by clicking on the clients on this Starlight Runner page.)

But most of what Gomez talked about in his Reinvention Summit 2 session (essentially a conversation with Reinvention Summit founder Michael Margolis) was people — individuals and groups — creating story worlds into which to invite other people.

How and under what circumstances might someone want to create a story  world? Growing up, Jeff learned to do so as a survival tactic, as part of a quest to find happiness. Today, he points to a democratizing participative narrative in which groups, using technology as a tool, poke holes in the dominant narrative and create a new story. Here, he cites examples such as the Arab Spring protests, and the activism that effected change surrounding controversies over Planned Parenthood and the proposed SOPA/PIPA legislation.

world? Growing up, Jeff learned to do so as a survival tactic, as part of a quest to find happiness. Today, he points to a democratizing participative narrative in which groups, using technology as a tool, poke holes in the dominant narrative and create a new story. Here, he cites examples such as the Arab Spring protests, and the activism that effected change surrounding controversies over Planned Parenthood and the proposed SOPA/PIPA legislation.

Jeff, he says, came into the world with many strikes against him. He was born to a single mother and with a facial paralysis that left one side of his face immobile. He was placed in foster care, in a nice home in which he experienced unconditional love for a few years. He saw a way of existence that stuck with him for the rest of his life.

Eventually his mother reclaimed him, and he lived in projects of New York City, in an environment he describes as dark, negative, and violent. He was bullied and kicked around. (Here, the summit participants suggested that bullies are the way they are because they have not been able to express their stories. “Maybe the core of a bully is someone who can’t get their story out,” said one attendee.)

Because of his early imprinting in the loving foster home, Jeff knew his life didn’t have to be that way. Though he found it difficult to make connections and build relationships, he plotted a strategy to make those connections to be happy again. He knew there was a different way to be and asked, “Why can’t I have that again?”

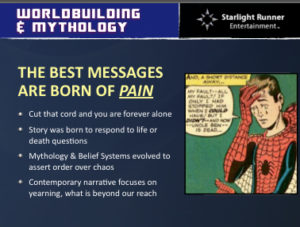

His pain was the setup for his own story. Though Jeff observes that plenty of storytellers don’t come from a place of pain, the truly timeless kind of entertainment springs from stories informed by the darker aspects of the human condition, he says; being an outsider who overcomes pain is foundational to the storytelling process.

In his youthful outsider world, Jeff was drawn to fantasy, mythology, comic books, and Dungeons and Dragons. Because he also didn’t want to grow up, Dungeons and Dragons became a tool to maintain a spirit of make believe. Realizing that D&D is a storytelling game in which players participate in the story, Jeff asked the tough guys in his neighborhood if they wanted to enter that world. Indeed, they came in and created characters, Jeff recalls.

The secret to getting them to come back was ask their aspirations. “What did they want to see in a world like this?” Jeff observed them experiencing something like reverie, reflecting on things they had never thought about. To get a tough guy to follow him, Jeff had to drop all pretense. and not see the person everyone else saw based on outward appearance. Jeff says he had to “start speaking to the person inside them I hoped they would be.” Jeff carefully integrated their fantasies into the game, engaging them on their emotional level, and writing them into the mythology. Jeff notes that this participatory approach harkens back to the earliest storytelling around tribal fires.

The secret to getting them to come back was ask their aspirations. “What did they want to see in a world like this?” Jeff observed them experiencing something like reverie, reflecting on things they had never thought about. To get a tough guy to follow him, Jeff had to drop all pretense. and not see the person everyone else saw based on outward appearance. Jeff says he had to “start speaking to the person inside them I hoped they would be.” Jeff carefully integrated their fantasies into the game, engaging them on their emotional level, and writing them into the mythology. Jeff notes that this participatory approach harkens back to the earliest storytelling around tribal fires.

At this point, we might ask, how can we incorporate this idea of constructing a story world — into which we can unite and integrate others — into our own lives? I feel the answer to that question for me is just within my grasp, but I’m not quite there. What if you are not as deeply steeped in fantasy, mythology, and gaming as Jeff is — as I am not? What if the “place of pain” in your origin story is really not all that painful — as mine isn’t? Sure, I’ve had painful points in my life, but not the way Jeff has and many others have.

Three years ago, I attempted to apply Jeff’s characteristics of a transmedia production to the notion of individuals and job-seekers using transmedia storytelling to tell their personal stories and brand themselves (here and here). I think I was somewhat on target with the transmedia part, but I largely overlooked the part about crafting a story world to begin with.

To do so effectively, we need to bring in mythology and archetypes, Jeff  says. He contends we also need a message. Because “every story has been told,” he says, the message beneath our concept has to really makes connections between the “property” (in this case the person) and audience. The “properties” that moves us are the ones where we connect emotionally with the story.

says. He contends we also need a message. Because “every story has been told,” he says, the message beneath our concept has to really makes connections between the “property” (in this case the person) and audience. The “properties” that moves us are the ones where we connect emotionally with the story.

Jeff talks about the Grand Narrative, the story that …

… reaches back to the dawn of humanity.

… contains wisdom and truth of human existence.

… filters through bittersweetness of own existence.

… embodies our collective human experience.

“Each of us is capable of shaping our own persona in a poignant way,” Jeff says. He raises tantalizing questions about doing so.

How might you construct a story world in your own life? How would you use that world, and how would you invite others to participate?