One of the most fascinating and provocative pieces of writing I’ve read in a long time was the text of a speech given by Leland Maschmeyer at a graphic-design conference at Princeton University. Maschmeyer was the only non-graphic designer to present at the conference.

Instead, he’s the director of strategy at a design firm. But he describes his job this way:

My take on it is that I’m a storyteller. My job is to find and tell the stories that I think my companies and my designers can become a part of and contribute to. This is a crucial function given that the stories we tell can change our orientation to the world, reframe our responsibilities and open opportunities we didn’t know existed.

Maschmeyer than proceeds to tell a series of stories aimed at changing his audience’s orientation to the world. I know he changed mine.

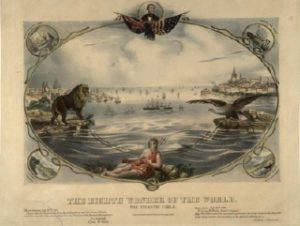

He begins with a historical perspective — 1860s London, an era in which breakthroughs such as laying the Transatlantic Cable were “a symbol of how man not only could, but WAS overcoming his physical limitations and the natural obstacles presented to him. This is probably why the copy [on the picture at right] reads ‘The Eighth Wonder of the World,'” Maschmeyer notes. He continues: “Oh yeah, and look at the heavily traffic ocean in between the countries. Each represents increases in commerce and national growth. All thanks to technology. The pursuits of industry, efficiency, productivity and scalability were the things that uplifted all of humanity. These were the most important pursuits of the day.”

By way of contrast, Maschmeyer then skips ahead to post-WWII America, when we began to sort ourselves into” ideological ghettoes,” becoming a nation of “self-focused collectives,” of which he gives numerous examples: plummeting memberships in social/charitable/service organizations, as well as in labor unions, and youth groups like Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts; the ballooning number of parents who are homeschooling their children, “shield[ing] their kids from community values, from community interaction and shelter them in an environment where the kids learn only what the parents approve of and show them;” dating services that cater to like-minded singles (e.g., conservatives); news broadcasts that are no longer objective overviews, but instead agenda-setting slants from a political perspective (e.g., Fox News for conservatives, MSNBC for liberals); giant shopping-mall-like churches with “campuses” that are communities unto themselves; and entire towns that share an ideology, such as (Ron) Paulville in Texas, which its Web site says comprises: “gated communities containing 100% Ron Paul supporters and or people that live by the ideals of freedom and liberty.”

Says Maschmeyer:

In our hyper-connected world where access to people and information have never before — in the history of mankind — been so easy, we are choosing to communicate with only the people and consume only the information that reinforces our worldview, sense of self and ideas. We are not communicating with the parts of the world that are at odds us.

The result, he says is “empathy deficit disorder.”

“… We cocoon ourselves in the information and people we want to see and read because they make us feel good about ourselves,” Maschmeyer says. “… But … without a commitment to amplifying empathy in the world, we won’t be able to achieve the compromises necessary to the collaboration necessary to overcome the environmental and social issues that plaguing our world. If we continue to live without empathy, we will continue to key our opponents’ cars and see other peoples’ problems as not our problems. Empathy is critical to our communication future.”

Now, Maschmeyer kind of loses me with his suggestion for transcending our ideological ghettoism, “relational art,” although Maschmeyer’s championing of 19th-century poet Matthew Arnold shows how art can broaden our horizons. Quoting from Arnold:

Art [can be] the great help out of our present difficulties: art turns a stream of fresh and free thought upon our stock notions and habits which we now follow mechanically imagining that there is a virtue in following in them.

So, yes, art can surely play a role in getting us to see beyond our “self-focused collectives.” It’s just that Relational Art, to me, doesn’t feel like nearly enough.

Still, Maschmeyer evoked change in me through his stories. I am certainly guilty of seeking out like-minded folks. In social-media venues, particularly Facebook, I am friends with some former students whose political views could not be more opposed to mine. When they express these views, I am often tempted to unfriend them. But after I read Maschmeyer’s speech, I realized I will be a better, more well-rounded person if I open myself up to other views.

This trend toward ideological ghettoism is dangerous but not much discussed. As global citizens, we need to be aware. Reading Maschmeyer’s speech — and stories — is an excellent start.