Two interesting concepts in visual storytelling have crossed my desk recently.

In a speech addressing criticism of 19th-century realist art, Fred Ross notes that 19th-century realists got a very raw deal — harsh criticism for lack of relevance — and should be appreciated: “The suppressed truth about this period,” he says, “… is that during the 19th century, there was an explosion of artistic activity unrivaled in all prior history. Thousands of properly trained artists developed a myriad of new techniques and explored countless new subjects and perspectives that had never been dealt with before. They covered nearly every aspect of human activity.” The most disturbing aspect of Ross’s piece, however, is that this snobbery about art that tells stories continues today:

Storytelling has become somehow a dirty word in the world of fine art. Storytelling is demeaned as mere “illustration,” and “illustration” itself is relegated to the “commercial arts.” Go sign up to study in the fine arts department of any college or university in America and tell the officials who run the place that you want to paint great anecdotal scenes, either as histories or allegorical paintings, that symbolize, capture, and express the most powerful of human themes.

What do you think will happen?

After looking down their noses at you while trying to figure out how to say what they want without insulting you, they will politely tell you, “Well dear, you really need to go and see the department of commercial arts.”

They will tell you that storytelling is not what they do. It doesn’t interest them. It’s not a fitting purpose for fine art. What is fitting? Form for its own sake, color for its own sake, line or mass for their own sake are far more worthy of accolades of merit than recreating scenes from the real world or from our fantasies, myths, or legends about our hopes, our dreams, and the most powerful moments in life.

Meanwhile, a recently ended art show in Miami is called “Denarrations,  Pan American Art Projects.” Critic Ernesto Menendez-Conde, writing in ArtPulse Magazine, explains “denarration:”

Pan American Art Projects.” Critic Ernesto Menendez-Conde, writing in ArtPulse Magazine, explains “denarration:”

… in denarrations, the act of analyzing, subverting, or even deconstructing narratives is an intrinsic part of the structure of storytelling. Denarrations are, therefore, paradoxical means of constructing narrations while dissecting, erasing or destroying them. If deconstruction is, above all, a tool for questioning the nature of philosophical discourses, denarration is primarily a tool for storytelling and structuring representation.

Pictured above is a piece from the Denarrations exhibition, Casa, (2009) by Jorge Perienes.

It’s worth considering both prejudice against storytelling in fine art and the denarration concept when viewing some recently talked-about examples of visual storytelling:

-

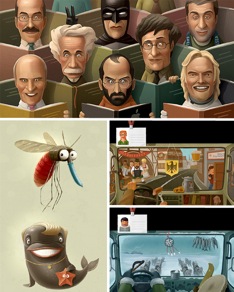

Two much-tweeted entries on My Modern Metropolis by “Alice” were 12 Masters of Visual Storytelling and 12 (More) Masters of Visual Storytelling. Pictured at left is In Da Car, which Alice cites in the first dozen, by Ashot Gevorkyan and Yaryshev Evgeny.

Two much-tweeted entries on My Modern Metropolis by “Alice” were 12 Masters of Visual Storytelling and 12 (More) Masters of Visual Storytelling. Pictured at left is In Da Car, which Alice cites in the first dozen, by Ashot Gevorkyan and Yaryshev Evgeny.- A similar piece is Art Meets Storytelling: 15 Amazing Illustrators on WebUrbanist by “Steph.” While Steph seems to use “artist” and illustrator” interchangeably, “illustrator” makes me think of Fred Ross’s speech and wonder if “illustrator” is a step down from “artist.” If you work in editorial illustration, comic books, video games and advertising as these artists do, are you any less of an artist? Pictured below is a selection by Andrey Gordeev.

-

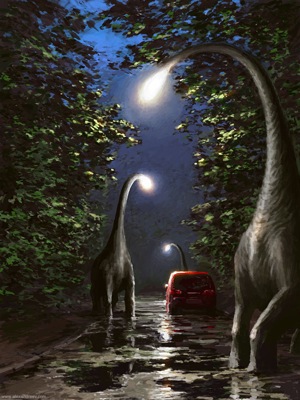

- Alex Andreyev has been cited as a visual storyteller. See what you think by viewing his portfolio. Pictured at right is July from the portfolio.

- Alex Andreyev has been cited as a visual storyteller. See what you think by viewing his portfolio. Pictured at right is July from the portfolio.