Time once again for one of my favorite pastimes, looking at ways to apply material about storytelling to the job search.

Today’s target is a posting about Donnie Claudino, TechSoup Canada’s marketing manager, who spoke at a conference about teaching charities about using online technology to improve their fundraising and marketing about how to use storytelling in online media. The post was written by “Andrew” on TechSoup.org.

Claudino used storytelling to land a job when he, as an American, wanted to immigrate to Canada.

Key to his storytelling message was the exhortation to know your audience. In the job-search, you must know as much as possible about your audience, the employer. Claudino notes you must “determine what action you want these people to take;” in the job search, you want you audience to invite you to the next step in the hiring process — whether interview, next interview, or job offer.

The “questions to ask yourself about your story” that Claudino proposes can easily be applied to job-search stories:

- Is the story transformative? Does your story have “heart-fire?” Does it have emotional pull? Is it believable and honest? [A story that shows your passion and enables the employer to become emotionally invested in you as a person and prospective employee will go a long way toward getting you the job.]

- Does it make [the employer] want to do something? Is the story inspirational and [can it] move [the employer]? More importantly, is there a clear course of action? [Hire me!]

- Can the story be repurposed? [In your cover letter, can you expand on a story you told in a clipped bullet point in your resume, and in your interview, can you expand on the same story even further? Can you re-purpose the story in networking situations, your career portfolio, and in a personal branding statement?]

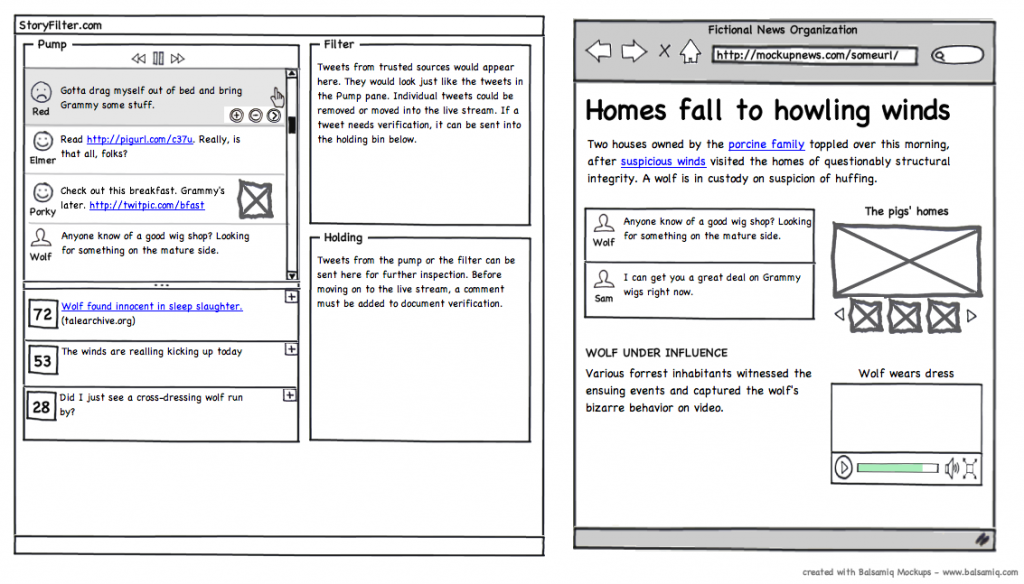

Suggesting that stories can “live” online, Claudino says, “The best strategy is to have a connected and consistent message in as many places as possible but which ultimately drives visitors back to a site to take a specific action.”

That’s why it’s a great idea for job-seekers to tell their stories on a personal Web page with their name as the domain name (like my katharinehansenphd.com). The Web site can introduce an online portfolio, full of stories of accomplishments and results. In addition to — or instead of — his or her own Web site, the job-seeker can have story-rich profiles on sites like LinkedIn. Contact information should be readily available so the employer or recruiter can take the specific action of getting in touch.