See a photo of Thaler, her bio, and Part 1 of this Q&A

Q&A with Thaler Pekar, Question 2:

Q: How important is it to you and your work to function within the framework of a particular definition of “story?” (i.e., What is a story?) What definition do you espouse?

A: I find the most useful framework for beginning story sharers is that a story has a beginning, middle, and end. I work with incredibly smart leaders who, when I initially met them, were often reluctant to share stories in professional settings. Precisely because they recognize the power of great storytelling, they were hesitant to share their stories — they didn’t think they possessed a perfectly polished, fleshed out, protagonist/compelling conflict/earth-shattering journey/surprising resolution tale to share.

The quest for the perfect can be the enemy of the good!

I energize leaders (and, in turn, their audiences), by helping them surface their passion and become the most authentic and persuasive speakers possible. Through several short exercises, I help these bright people see that they are telling stories all day long, and that they possess a lifetime of interesting anecdotes and a multitude of fascinating, powerful stories. To this end, the only story framework I encourage beginning story sharers to use is “beginning, middle, and end.”

Then, details that reveal emotion, and trigger the senses, are added. And

then conflict, resolution, and transformation.

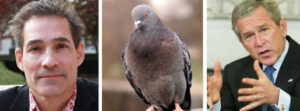

I’ve always known that conflict is a critical element in story. But I recently had an epiphany about how even the slightest frame of conflict enables a fact to stick in a listener’s mind. At an event in the “Brainwave: It Could Change Your Mind” series at the Rubin Museum of Art, George Bonanno, Columbia University psychology professor and expert in emotion, stated the fact that birds share more computational language skills with humans than our closest primates.

This fact alone was new and interesting to me. But Bonanno added that former President George Bush, who was “unfriendly to science,” cut funding for a perhaps silly sounding, but quite scientifically important, study of Pigeon Language Cognition Skills.

Adding this point of conflict turned that fact into a story. Bonanno provided a great example of how to take a fact, add a conflict, and make the fact memorable.

Adding this point of conflict turned that fact into a story. Bonanno provided a great example of how to take a fact, add a conflict, and make the fact memorable.